Subscribe to continue reading

Subscribe to get access to the rest of this post and other subscriber-only content.

I am exploring how to become the best version of humanity.

Subscribe to get access to the rest of this post and other subscriber-only content.

Subscribe to get access to the rest of this post and other subscriber-only content.

I’m taking a mini detour from my series on Understanding Responsibility and the Impact of Actions to write on confidence.

It starts with fear. ‘I can’t do it,’ the voice in our head whispers. The mind hesitates and almost stutters out a ‘but…,’ but the voice continues with a more trivial reason ‘I am not tall enough, they need six feet, I’m only 5.6.’ ‘I’m shy.’ ‘I’m socially awkward.’ ‘They’ll come to see me as who I am — the impostor.’

And what’s more, the more we present this person to the world, the more we become it, the ‘socially awkward’ boy, the ‘not tall enough’ girl, ‘the impostor,’ and the list goes on. We are who we say we are.

If I didn’t define myself for myself, I would be crunched into other people’s fantasies for me and eaten alive.

Audre Lorde.

I have often dined with fear. It was my default reaction when I faced uncertainties; I know how crippling fear can be when we aren’t sure about anything; I can even describe the taste — salty, metallic, bitter — when fear becomes anxiety. I’ve found that this state of mind often leads to unhealthy reactions to situations.

Fear does not appreciate the light of awareness. When we call fear by its name, we acknowledge its presence, enabling us to approach the situation with vulnerability and proactivity in seeking solutions. Calling the problem its name allows one to start from a place of vulnerability and gratitude and arrive at forgiveness and clarity with trust in oneself.

Fear dampens confidence. When we let fear in, we become our fears, often hindering our ability to function in the presence of struggle. I’ve felt fear varying from ‘what if nobody wants to listen to me?‘ ‘what if I’m unable to provide for my family?’ I’ve found that in most situations, this fear has always been less about myself and more about others and what people will think.

I am careful not to personalise fear, for when I say ‘my fear,’ it becomes true — my fear. Instead, I express it as ‘I feel fear.’ ‘I have a fear.’ ‘The fear I’ve felt.’ This way, I’m acknowledging a state of emotion that isn’t identical with my identity. This approach helps me see this state as a visitor just here to visit, and should be on its way soon.

I have a fear, and I find that when this fear comes up in my head, I become less confident and start to stutter. The people closest to me could write a series about it. Others, however, remain oblivious unless I open up. Then, they struggle to fathom how someone perceived as ‘bold‘ as I could ever be shy.

People see me as extroverted and wonder what I mean when I mention that I struggle with talking. Just being able to articulate my thoughts and express them to others in a large social setting drains my body of energy. A colleague said it was difficult to believe I had such struggles because I didn’t show it, and I responded that I hid it well.

Each time I unmute my microphone, I battle between making my voice ‘heard’ enough and the voices in my head asking – ‘Is my voice strong enough?‘ ‘Am I making sense?‘ ‘Do these people want to listen to me?’ ‘Am I losing them?‘ ‘Uh oh, are they about to interrupt me? Have I stopped making sense?‘

So, when I started the new year, it wasn’t surprising that my journal entry was ‘I will use my voice more.’

I realise it is not easy to tell someone to be brave and confront their fears without telling them how to. The concept of bravery, as explored in my previous work, extends far beyond merely overcoming fear. At that moment, fear is all they can see; it is all that exists. I have been on both sides of the tunnel: the fearful person and the person dishing the advice. We must also remember to listen to ourselves when we dish out these bits of advice.

Whether you think you can, or you think you can’t — you’re right.

Henry Ford

If we surrender to fear, we remain where we are, stranded, stagnant. Someone who is afraid of taking the plunge to study for a new course that would take four years to complete because they think there’s no time is correct.

There’s no time if we say there’s no time. However, four years is always in the future and will eventually come. Start today, and in four years, this person will be on the verge of completion, but start later, and it will still take four years.

The next time the thought of fear comes, slow down to reflect on where you were several years ago. If you could have taken a step toward your goal back then, imagine where you could be now. Now, project yourself into the future and consider if you would regret not starting today. What’s the worst that can happen? Let these reflections spur you to action.

Fear blames because it needs an outlet to move responsibility away from the self. It finds another, who is responsible, constantly referring to the past or someone whose fault it is they can’t take responsibility in the moment.

Fear prolongs suffering.

Fear hinders our progression to the next stage. It presents a situation as ‘the obstacle,’ rather than puzzle pieces. It complicates matters, not just for us but for everyone in our lives.

Fear makes it difficult to stay grounded in the present, as it continually catapults us into a non-existing future, thus disabling our ability to see and appreciate what is happening in the present.

Many of us face fear; not even the CEO of the biggest company in the world is immune. We all have demons that keep us awake deep in the night and leave us restless long after sleep has fled. Those tiring days filled with wishes, prayers, hopes for things to be different, and anxiety about the future.

Yet, we are here, still grappling with fears, albeit new ones. If only we could look back in gratitude and see how far we’ve come.

‘beloved’ is both verb and noun, both identity and instruction. Fear is an affront to your spirit, so don’t be scared, be loved.

Moyosola Olowokure

The above quote illuminates love as the antidote to fear. When love takes over, everything feels alright — even though everything has always been okay — we just had not realised it.

Suddenly, everything becomes light and free. Freedom comes with love and clarity, bringing a new wave of confidence. We transform, becoming captivating with a new sense of allure, and in the process, we discover a new version of ourselves.

Fear is the greatest deterrent to confidence. Confidence is on the other side of fear; I searched for the synonyms and found the following:

assurance, self-assurance, self-confidence, self-reliance, self-esteem, boldness, certainty, conviction, trust, faith, positivity, poise, assertiveness, sureness, fearlessness, courage, self-trust, belief, security, composure.

The term ‘confidence‘ comes from the Latin word ‘confidentia,’ which means ‘trusting in oneself.’

Many people have reached where we aspire to be primarily because of how confident they are in themselves. They might not be more qualified than us, yet, like a butterfly with its vibrant and bold display, their confidence is immediately captivating.

Charmed by the butterfly’s radiance, it’s easy to overlook the reticent worker bee diligently making honey or the unassuming wallflower producing nectar. Yet, it’s important to remember the butterfly itself isn’t the source of the nectar enhancing its allure.

We must remember that hard work, resilience, and talent form the basis for long-lasting confidence.

By recognising our fears and calling them by their name, we bring them into the light and take responsibility for them.

We take responsibility by first slowing down to give gratitude for where we are coming from and the clarity of knowing that something is wrong and then committing towards bringing ourselves to the spotlight through curiosity and an action plan.

In my case, I began to assert myself more within my circles. In my community, I started leading some of the weekly meditation and Sunday gratitude sessions on ClubHouse. I also started participating more in the conversations. I’m not there yet, but I’m using my voice more.

Growth is uncomfortable; it’s like working a tight muscle until it stretches. I remember feeling uncomfortable the first time I turned on my camera during a video call. Now, it feels awkward to have a call with the camera off.

When we can address fear by its name, we’ve taken the first step towards light, and thereon, we can find ways to work out a solution. In time, we realise that it isn’t even all that bad.

In the words of Moyosola Olowokure, ‘Fear is an affront to your spirit. be loved.’

Fear is passive, stagnating our spirit, while love and confidence—emotions synonymous with action—propel us forward. Fear avoids action, whereas our spirit inherently thrives on doing. As we immerse ourselves in action and curiosity, we push back against fear until it becomes a mere shadow and a distant memory.

As Sang Zhi aptly puts it in my recent favourite series, ‘Hidden Love,’ ‘after all the bad things are over, all that is left are the good things. So, from now on, you must be even more certain that you are the best.’

You must be kinder to yourself. Affirm this to yourself that you are the best in the world, and no one can tell you otherwise.

Thank you so much for taking the time to read this piece. What fears do you carry with you? More importantly, what strategies have you found effective in combating these fears? Please, share your experiences and insights in the comment section. Your story might be the encouragement someone else needs.

In part 2 of this series, I introduced the concept of responsibility at individual and social levels. In this chapter, we delve into the crucial role of intention in responsibility, underlining the importance of conscientiousness even in the littlest tasks.

People are constantly watching how we act. We may not know it until we reach out to others to recommend us for a role, and we feel dismayed when we catch a hesitation in their demeanour or pleasantly surprised, depending on the situation.

We ponder the reason but cannot ascertain why they passed us for someone else on the job; this is akin to LinkedIn recommendations; there, when we endorse someone’s skills, we affirm our belief in their abilities and capacity to excel.

When someone recommends another for a role, they automatically take responsibility for the person they recommend. If that person falls short of the endorsement, the recipient may hesitate to seek future recommendations.

Hence, we want to give our best when it’s time for us to put someone forward because we are entering into a trust with the recommended and the recipient of the recommendation. But before we get to this stage where people ask for our thoughts in recommending another, we start from within by building ourselves towards being worthy of becoming recommended.

If a man is called to be a street sweeper, he should sweep streets even as Michaelangelo painted, or Beethoven composed music or Shakespeare wrote poetry. He should sweep streets so well that all the hosts of heaven and earth will pause to say, ‘Here lived a great street sweeper who did his job well

Martin Luther King Jr.

When I think of ‘responsibility,’ I think of action imbued with ‘good work.‘ An adage in Igbo goes, ‘Ozi adịghị nwata mma, o je ya nje na abụ.’ The literal translation of this proverb is: ‘If an errand is not good for a child, the child goes on the errand twice.

I grew up hearing my grandparents and older aunts and uncles use the above phrase to emphasise the role of intention in responsibility.

This literal translation encapsulates a specific thought process from the Igbo culture: if a child believes an errand or ‘responsibility’ is beneath them and, as a result, does not perform it well initially (perhaps finding various ways to avoid the task), the sender will ensure they repeat the errand until they execute the chore satisfactorily. In this context, whether the errand is deemed suitable for the child is decided by the adult and not the child.

For instance, if an adult sends a child to buy crayfish from the market, and the child throws a tantrum for about 30 minutes, gets distracted playing street football, and comes back 2.5 hours later with Moi Moi instead, the sender would wonder about the relationship between Crayfish and Moi Moi before sending the child back to the task.

Sending the child a second time to the market might not be all the repercussions the child has to bear from the task assigned to them. The sender may also have to punish this child to instil some sense of value, discipline, and responsibility in them.

Your work is going to fill a large part of your life, and the only way to be truly satisfied is to do what you believe is great work. And the only way to do great work is to love what you do. If you haven’t found it yet, keep looking. Don’t settle.

Steve Jobs’ 2005 Stanford Commencement Address

Performing a role with good intentions means seeing a task as not just an assignment, but an opportunity to take ownership and make an impact. Some people call it ‘the calling.’ The calling is why many influencers advocate for making our passion our job. Steve Jobs called it ‘doing great work’ and endorsed it in his commencement address to the 2005 set of Stanford graduates.

The energy and dedication we bring to this responsibility and how we respond can significantly influence the outcome. Expressions such as ‘you did it with so much love, are not merely feedback; they highlight the tangible impact of our heart-filled efforts.

This connection between intention and output was something I grasped at an early age. I remember an instance from childhood when, after tasting a meal I had prepared, my uncle queried, ‘Ifunanya, were you in a bad mood when you made this?’ I cannot remember my emotional state at the time, but his question underlined a truth that has stuck with me: our attitudes and intentions, even when unseen, leaves an imprint on our actions.

Nigerians use ‘yeye dey smell. When breeze blow, fowl nyash go open‘ to convey that nobody can hide the truth. Just as the wind can blow to expose what the chicken was sitting on, so too can life events reveal the true intent behind an action.

Consider the case of renting apartments in Lagos, Nigeria. Lagosians share an experience of inheriting house issues from a newly rented apartment. Property owners often build their houses with substandard products that break easily and cause a lot of frustration for their occupants. Eventually, when this occurs, the landlord ends up being equally affected, as was my case when one of the toilets in my house broke and had to be knocked down and rebuilt. The previous one kept leaking water into my neighbour’s apartment downstairs, and it became messy. Eventually, my landlord’s attempt to save money by building with less quality materials became futile, as he lost more money due to the repairs. I have lost count of the numerous issues I have faced in my current house: from leaking toilets to leaking walls, to a leaking roof, to faulty electrical appliances, to a shaky floor. At one point, I wondered if my apartment would fall on me. One of my neighbours left before his one-year rent was due, and nobody has called to check on the house since he left.

A recurring question around moral consequences is: if someone will eventually have to fulfil a responsibility or a role, either assigned to them or chosen by them, out of duty or for their profession, should they not approach it with good intentions?

In a world where our actions echo louder than our words, our intentions shape the resonance of our responsibilities. As we journey through life, it is crucial to remember that the ‘tasks’ we deem beneath us today could well be the stepping stones for tomorrow’s triumphs. Let us embrace Steve Jobs and Martin Luther King Jr.’s words, striving to approach our role, no matter how routine or small, with love, good intentions, an open heart and a focused mind, recognising that our responsibility speaks to our character.

Thank you for reading. I hope you enjoyed this section as much as I did writing it. The next part will explore the role of action and reason in responsibility and how we can move together as a community.

In part 1 of this series, I shared a personal struggle that inspired this reflection on responsibility, intention, and action. Now, let’s delve deeper into this sensitive topic that carries so much weight in our lives, relationships, and societies.

The topic of responsibility and intention holds dear in my heart. I have initiated numerous conversations with those willing to engage, seeking to understand the root of neglecting responsibility, evasion of fault and explain why it matters in every relationship.

From first-hand experience, I understand that when someone avoids taking responsibility, someone else must shoulder the burden of that action, which means bearing responsibility for another’s irresponsibility. Many may resonate with this, as I have often found myself playing the role of the person who has to take responsibility for someone else’s inactions.

We witness a lack of responsibility in different contexts; in the professional setting, when an employee fails to fulfil their task, someone else must step in to complete the work. Outside work, when a child, sibling, spouse, friend, or parent neglects personal responsibility, others around them may feel obligated to step in; this could be a sibling who cleans up after another, a friend who excuses their friend’s behaviour, a spouse or parent who covers their partner’s or child’s mistake, or even a child stepping in for a parent.

These situations depict the ease with which responsibility can transfer from one person to another. This dynamic raises significant questions: to what extent should individuals continue to shoulder additional burdens on behalf of others, and how can we motivate others to assume responsibility for their actions?

Responsibility is a duty associated with our actions. The Cambridge Dictionary defines responsibility as ‘something that it is your job or duty to deal with.‘ This concept refers to an expectation or obligation to act in certain ways to achieve particular outcomes. Responsibility prompts questions such as ‘What do I need to do?’ ‘What is expected of me?’ and ‘What choices must I make in this scenario?’

Responsibility can take many forms, and we can categorise it into direct or indirect. Direct responsibility encompasses duties and obligations we assign ourselves, which stems from past decisions and choices. They are more individualistic, originating from personal decisions made independent of others. These might include personal goals, self-improvement tasks, or commitments we make to ourselves. Direct responsibility could vary from exercising regularly, starting a course to more complex ones like starting a family and raising a child.

In contrast, indirect responsibility involves duties assigned to us by others, typically related to our occupied roles. These responsibilities may result from our social roles, societal norms and expectations, or tasks assigned to us by others. In our professional lives, these might include tasks assigned by a manager or responsibilities that inherently come with our job role. In our personal lives, these could be duties or roles associated with being part of a family or community, like caring for a sick family member. These responsibilities are generally less voluntary and more prescribed by our circumstances or others.

Individual responsibility plays a crucial role in every functioning system. From the intricacies of a bustling city to the regimented societies of ants and bees, if a single cog in this machine fails to fulfil its duty, the entire system is at risk. This principle applies to a worker bee gathering nectar as much as it does to a human maintaining essential utilities.

Consider the role of an obstetrician in a local clinic responsible for delivering a baby. A delay or failure in their job can endanger the expecting mother’s life. A visiting surgeon, faced with a coinciding surgical operation, may have to make difficult decisions. If the mother is in distress and the surgeon’s other patient isn’t too critical, the surgeon might extend her schedule to assist with the delivery. The ripple effects of these decisions and outcomes can significantly impact multiple lives.

In the animal kingdom, the roles of workers, soldiers, and breeders in ants, bees, and termites, or hunters, defenders, and babysitters in wolf packs, are all crucial for survival. While it’s often argued that animals lack moral judgment, with actions primarily driven by instinct, nature, and the imperative to survive and reproduce, they still reflect a form of responsibility essential to the survival and reproduction of their species. However, in human societies, the concept of responsibility goes beyond basic survival, involving moral and ethical implications.

As we turn our attention back to human society, we see that acceptance and execution of responsibility are integral to the smooth functioning of our communities. When an individual assumes responsibility, they accept accountability for their actions. This acceptance contributes to trust, fairness, cooperation, and mutual respect for those involved.

Consider two examples of internal dialogue:

These examples showcase two individuals with different goals and values. The first person sees the need to do their job well to earn customer trust. The second person contemplates the practical implications of not studying, linking it to their broader life goal of helping their family.

Individual responsibility often starts when one can link their choice to their purpose, as illustrated with the two individuals in the dialogue.

In line with the saying, ‘charity begins at home,’ it stands to reason that one cannot assume responsibility for another without first taking responsibility for oneself. Hence, direct responsibility feeds into indirect responsibility, and in this way, we move from the ‘I’ to the ‘altruistic.’ Personal responsibility can evolve into a broader, altruistic responsibility toward others in our community.

Let us also consider different scenarios involving two adults and a child in varying environments.

If two adults mutually decide to start a family, they share the responsibility for nurturing any children that result from this decision.

There will be expectations for the child to perform some familial roles and for the family members to be responsible members of their community. By becoming part of a society, we inherit responsibilities like understanding and adhering to social norms, being considerate and respectful of others, and contributing to the community. Nonetheless, being a responsible member of society is a continual journey of learning and personal growth, necessitating a commitment to the shared principles of justice, fairness, and mutual respect.

Thank you for reading. As we progress in this series, I encourage you to reflect on your understanding of responsibility. How do you view your responsibilities, and how do they influence your societal roles? Share your thoughts in the comments below. In the next part of this series, we will delve deeper into responsibility, exploring the role of intention, action, and reason and discussing how we can move together as a community.

This story marks the beginning of my reflections on responsibility, intention, and action. Stay tuned for the rest of the series.

The Broken Pump and the Waiting Game

As I write this story, I use all my willpower to stay strong and not succumb to the urge to use the bathroom. I find myself hoping, praying, and willing the plumber to arrive, as I had successfully gotten through to him 22 minutes ago when he called me to ask the estate security to let him in.

I hear the sound of the gate and peep through my window; it is the plumber, who I will refer to as Mayowa for the sake of this story.

Mayowa was not new to our house; we had inherited him from our landlord shortly after renting the apartment. With the numerous issues that came with the house, we always brought them to the landlord’s attention; his immediate response was, ‘Ifunanya, I have called Mayowa. He’s on his way.’ And yes, he would be on his way, but often 9 hours after he had promised to arrive.

I sigh with relief. I might be able to hold on for another 30 minutes. Or perhaps an hour? I attempt a rough calculation of how long it will take to fix the pumping machine – Argh, I am not sure. I can’t make a reliable estimate. But whenever Mayowa and his companion are able to fix it, it should take another hour for them to pump the water up before it reaches our apartment.

Frustration courses through me as I grapple, yet again, with the bitter reality of broken promises.

This experience was not how I envisioned starting my exploration into responsibility. I have numerous tabs open on my browser, filled with materials to guide my understanding of responsibility, motives, and intention – all to support my narrative on the subject: ‘Understanding Responsibility and the Impact of Actions.’

Argh, where was I?

By 08:00 AM, I had phoned Mayowa to follow up on his plans to install our new pumping machine. The old one had failed yesterday, leaving us without water. Mayowa had come to pick up the broken machine, promising that if he didn’t manage to return with it repaired yesterday, he would undoubtedly be back to install it this morning.

When I called him, I had hoped he would be on his way. Alas, he was not. He had taken the machine to someone else to repair it – I don’t understand this other person’s role here. However, Mayowa was going to retrieve the pumping machine from him by 10:00 AM, as agreed between them.

The Struggles of a Night Without Water

The waterless night was a challenging ordeal. Having gone to bed without bathing and after multiple attempts to use the same unflushed toilet, I finally reached a breaking point and couldn’t bring myself to do it again. So, I peed in the shower each time, using the remaining water in the bucket to rinse it off. The pee smell was beginning to ooze through the closed doors as my bowels rolled uncomfortably, pressing me with the urge to relieve myself.

However, I survived the night, mostly.

The Broken Promise and Unmet Expectations

At 10:00 AM, I phoned Mayowa to confirm we were on track. He was on his way to meet with the person. I hung up, counting the time he would get there and here. I called at 11 but was disappointed to hear the man hadn’t started whatever he was supposed to do with the machine. His excuse was that there was no electricity. After hanging up, I followed up with Mayowa every half hour, and his excuse was more elaborate than the previous one.

His responses varied from ‘Madam, the man is almost done’ to ‘I’m on my way.’ At 1:00 PM, he was on his way. At 2:00 PM, he claimed to be at my estate entrance, but by 2:30 PM, I couldn’t reach his phone. At a point, I prayed he wasn’t involved in an accident. At 3:00 PM, I slept off with my phone in my hand, praying that I don’t develop a condition for not going to the toilet. When I woke at 4:00 PM, I rushed to my bathroom sink, holding my breath as I turned it on. A sinking feeling came over me as I realised that the water trickling from the tap was just residue from the previous pumping.

Mayowa had not come. I found myself pondering my next move: should I lodge my family in a hotel? But the expense would be astronomical!

At 4:09 PM, Mayowa’s call came in. ‘Ma, please, call your gate for me.’

I hissed.

I let myself write for a while after hearing Mayowa enter our compound to slow down my whirring thoughts. I was determined to confront him about his lack of responsibility, which is starting to seem like my favourite topic. It is okay to be angry, I say to myself, but I was not going to let my anger get the better of me. I will express myself clearly and let him see why I am angry.

Confronting Mayowa and Contemplating Responsibility

Finally, I went downstairs, and as I shut the door, my eyes met with Mayowa’s as he broke into a smile. I didn’t know what to make of the smile, so I asked in a voice that almost gave away my emotions, ‘Mayowa, why are you smiling? I am angry with you.’

He immediately started talking and apologising about how it wasn’t his fault, but I wouldn’t let him.

‘Mayowa, it is your fault. When you left this compound with the pumping machine, you became responsible for it. I trusted you when you said you were coming in the morning. But from 10:00 AM to 4:00 PM? No, this is not how we do things.’

I am waiting upstairs, in my room, as they fix the pumping machine downstairs. I hope and pray with all my might that the Power Holding Company of Nigeria (PHCN) will not suddenly cut off the electricity; it will be heartbreaking if that happens.

And shortly after I wrote the above, the power went out.

I smile bitterly. It’s 5:05 PM.

I ponder on Mayowa’s defence – ‘It’s not my fault.’ This denial reminds me of the old nursery rhyme – ‘Mr. Nobody.‘ In this rhyme, ‘Mr. Nobody,’ an unseen character, is always responsible for all the mischief in the neighbourhood. Mayowa had become a real-life ‘Mr. Not-My-Fault,’ refusing to acknowledge his role in the situation.

I can’t help but wonder: if it isn’t Mayowa’s fault, then whose is it?

As I sit here waiting, still without water, I realise that understanding responsibility is a lot more complicated than it seems.

Thank you for reading. In the next part of this series, we will explore the concept of responsibility and how it can play out in various scenarios.

When we say ‘forgiveness,’ we often forget that forgiveness should start from within. For us to forgive another, we must first forgive ourselves.

We don’t realise how much bitterness and resentment we hold within ourselves until we face a similar situation. Over time, this bitterness grows into fear, walls, and biases, making it challenging to embrace a different path. But to move on, we must first forgive ourselves.

To forgive ourselves, we must first acknowledge what happened. Sometimes, these mistakes are not ours to bear; however, because of the expectations we place on ourselves to be perfect, we fail to see past the current situation. We say to ourselves, ‘never again,’ and shut ourselves off. Because we never confronted the first situation, we may find history repeating itself as this bitterness grows deep and imprints itself into our hearts, creating burdens we need to release.

Years later, we become a product of our traumas, unaware that we hold these biases unless someone calls them to our attention.

Some years ago, my friend called my attention to a prejudice I held so tightly that I didn’t even realise it was there.

What are the beliefs we hold as truths that are actually prejudices?

Just because I’ve had similar experiences with people of a certain gender in the past doesn’t mean every individual of that gender will act the same way in the future.

What happens with biases is that when we hold on to them so tightly, we close ourselves off from a part of the world. In my case, any man driving a car who stops me on the road must want something more. I couldn’t believe I held on so tightly to this mindset, thinking it was the absolute truth. I even mentioned this to my sister on our walk.

How long had I closed myself from love, friendship, or connection because of this bias?

I wept when I finally faced the truth I had been trying so hard to avoid because I felt so guilty that I had to talk to my friend about it. I let myself cry for all the hurt I’d been holding onto; for not loving myself enough to realize that I needed to forgive myself, and for being rude to a stranger whose only crime was stopping me on the road to ask for my friendship.

What follows from here is love, lessons, forgiveness, and self-compassion; love and forgiveness that comes from within; lessons learned from the incident; and a promise to be more open-minded. In this experience, we remember to be kind to ourselves as we work on moving forward.

‘We are a product of our traumas,’ my friend, Biodun, says. ‘Our traumas shape us and make us who we are.’

Imagine we give ourselves time, love, and care to forgive ourselves, learn from our situations, and move forward. Imagine we acknowledge that it is not our fault that these traumas happened to us. And imagine we write the future with so much love bursting through us as a byproduct of the lessons we learned and the love we allowed ourselves to feel and produce when we didn’t let that incident define us. We become love, telling love stories with kindness, passion, and sincerity towards others we meet on our way.

Last December was a myriad of events, as we were all exhausted from the spike in ridesharing fees, congested traffic, and fuel shortage. On this day, we walked a long distance from our house to catch a bus at the junction and then walked even further from the bus stop to the hospital because it was during this time that my brother was ill. After seeing the good doctor, we walked a good kilometre to reach the next bus stop, and it was here that we encountered what was going to be our fate for the next few minutes.

A keke driver appeared, as if by magic, with one passenger on board.

“Ojota!” we screamed in excitement, as it was almost too good to be true. Other buses that had gone by either needed only one passenger or none at all and many people were waiting at the bus stop. We were already on our way from the bus stop as we’d resolved to continue the journey on foot or if we were lucky, we’d find a suitable vehicle to take the four of us. We quickly got in as the vehicle slowed down. “Wole, (Enter)” the driver screamed in pidgin. “Enter sharp sharp, dem dey arrest keke for here! (Enter quickly, they’re arresting keke drivers here)”

We jumped in. My brother Newman and I got into the keke, followed by Bobo, who took the front seat. However, another passenger was already in the vehicle, and the seats were not going to be enough for all of us. The driver, acting as if he was in a hurry, instructed my younger brother Neche to sit on Newman’s lap. The driver had previously apologised for the inconvenience caused by the extra passenger, saying that the man would come down ‘up there.’

In horror, I blurted to the driver. “He’s sick, he can’t carry him.” I didn’t realise what I had said until the driver retorted in pidgin: “how I wan take know? My own na mek him enter, mek we dey go. (How could I have known? I’m only interested in moving this vehicle).“

Of course, how could the driver have known that we were just coming from the hospital?

Newman lapped Neche, and laughter bubbled up from within me, as I shook my head at my own silliness.

“Na true, you for no know. (That’s true. You couldn’t have known)” I responded in a voice that sounded almost like a whisper, in pidgin.

This was me in my element, surrounded by family, full of excitement, and almost forgetting to breathe.

After about two minutes, which felt like ten minutes, I heard the driver ask Newman for a rag behind him. I turned to look at the rag and noticed how dirty it was and wondered if I had my hand sanitiser in my tote bag.

But that was not what Newman was thinking. In fact, I was not privy to Newman’s thoughts until we got off the keke. The events that followed seemed like something that happened in movies. Because I later found out that Newman reached into his right pocket, pulled out his phone, and held it in his other hand before grabbing the rag for the driver from the booth.

Just before reaching the Coca-Cola roundabout at Alausa, the driver suddenly became manic. “Na for that hill I go drop una. I no dey reach Ojota bus stop o. If una want, I go drop una for here, give you change. (I will drop you people at that hill. I’m not getting to Ojota. If you want, I will stop here and give you your change.” In a calm voice, still oblivious of what had happened or was happening, I asked, “Which hill? I’m sure we can get off there.” Neche started to add in Igbo, “Ify, do you know that place where…”

Out of the blue, I heard Newman say in his calmest voice, “Ifunanya, don’t argue. Listen to me. Collect the change and let’s get off here.”

The manner in which Newman spoke caught my attention, and I listened without arguing, which was unusual for me, as I would typically argue with my brother. But, oh well, he called my full name, and anytime he does that, he means business.

We took the change and got out of the keke. The driver then quickly drove away with the other passenger.

Newman explained what happened then. The driver had used an “old scope” to try to distract him. When the driver asked Newman to grab the rag from behind him, the thought was that this would cause Newman to turn and thus be momentarily distracted, which would allow the other passenger the opportunity to try and steal Newman’s phone by slipping his hand into Newman’s pocket. However, Newman was alert and had noticed the passenger’s attempt to steal his phone because the phone was nearly half an inch away from his pocket then. The driver and his accomplice didn’t expect that Newman was familiar with the scope as pickpockets had tried this tactic on him in the past.

Then he asked. “Did you notice that the passenger was still in the keke even though the driver had said he was going to drop soon?”

This experience with my brother was another crucial step in my ongoing journey towards mindfulness. For days, I would reflect on this experience, as I had been oblivious of this side of my brother. As I applaud his ability to slow down in that moment of need, I also recognize how difficult it can be to stay present.

Last year, I became a member of Akanka Spaces—an intentional community of people focused on nurturing a mindset of love, backed by the framework of intention. This framework teaches that everything begins with slowing down, followed by gratitude and responsibility. Adopting this mindset has helped me become more intentional in my life, allowing me to approach situations with a greater sense of purpose and understanding.

Sometimes, we are fully aware of a moment, and other times, we only realise it when someone or something calls our attention to the present, and I wonder how many of such times I have failed to recognise such moments. My answer is ‘probably a lot of times.’

A lot of times, I find myself acting impulsively and absent-mindedly. Much to my detriment, this happens more often than I am proud to admit.

If we can slow down to be present in the moment, we can catch these moments before they slip away. Otherwise, we may find ourselves acting in ways that we may later regret.

Awareness of these moments is a rare gift, and my brother’s actions served as a powerful reminder of its importance.

Since that day, I have made a conscious effort to be more present in my interactions with friends and family. I have discovered that by slowing down to pay attention and be aware of the moment, I can better understand and support the people around me. This awareness has not only enriched my relationships, but it has also allowed me to grow as an individual.

When I travelled to Ghana, I did not have a set plan of what I was going there to do or the places of interest to visit. My goal was to go to Ghana and see Mawuu. Perhaps, this lack of a plan was why I paid an expensive amount to reschedule my flight, as I had arrived late for check-in at the airport and could not move with my scheduled flight.

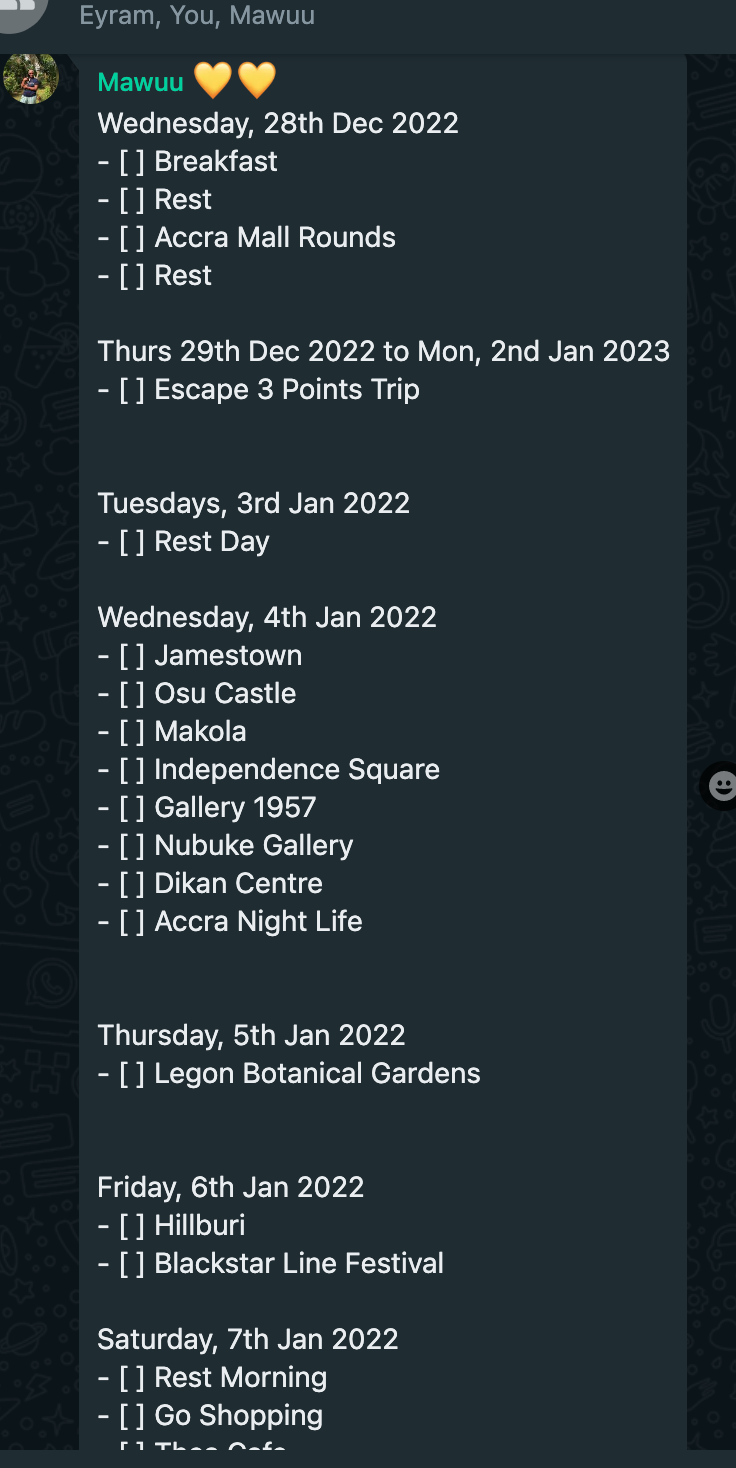

In the afternoon of the day I arrived in Ghana, Mawuu asked me if I had places I had planned to visit, and I responded in the negative. I was only going to meet with my colleagues later that day, and that was it. Oh, and then travel with the Travel Tribe to Southwestern Ghana; this was a plan that Mawuu had sold me when I told her of my plan to visit Ghana. As I bit into my brunch at Starbites Restaurant at East Legon, Mawuu drew up an itinerary on the spot for me and added me to a Whatsapp group with the subject – “Ify in Ghana.”

People gape at me in disbelief when I tell them this story of never having planned my Ghana trip. If only they knew that I had also borrowed the Ghana trip idea from my dearest friend, Doyin.

Initially, Doyin had shared the idea of going to Ghana to rejuvenate herself, and I welcomed the thought. Life was too short to overthink about doing something for oneself. My new ambition is to travel, and I would not waste time worrying about the details.

And when Doyin’s plan of travelling to Ghana changed, the thought of visiting Ghana stuck out like a sore thumb, that I could not shake off. Without further ado, I packed my bags and headed off to Ghana.

In Travelling Just For The People, Derek Sivers wrote of a friend who had travelled a long distance just to come and stay with him. When Derek asked if he had planned to visit any sights, he said No. “I don’t care what we do. I just came to see you!”

Bewildered, Derek probed him further, and he replied, “Dude. I’m serious. I really don’t care about any of that stuff. I came here to see you, hang out with you, talk with you. That’s honestly the only reason I’m here. You don’t have to take me anywhere or show me anything.”

Reflecting on that experience, Derek wrote, “I remember almost nothing but that conversation. Sometimes we connect with a place, but usually we connect with people. Yet people connect us to a place.”

Yes, people connect us to a place. My journey in Ghana crystallised at the airport – meeting Mawuu for the first time and Eyram for the second time – two lovely people whose souls introduced me to the heart of Ghana. This meeting would define the rest of my journey in Ghana, for when I think of this meeting, I think of old friendships and new beginnings, of laughter and warmth, of the vibrant colours and sounds of the people in closed spaces, and of the kindness and generosity of the people I would meet along the way.

And when I think of Flo, Sol, Nyash the cat, or the good old dogs – Whiskey and Charlie, I will remember Escape 3 Points for all its warmth. When I think of Escape 3 Points, I will remember all these and more – the Travel Tribe’s nightly conversations, the ‘good mornings’ that came with the question of ‘did you sleep well?’ the look of concern when one of the Travel Tribe members so much as breathed a cough, the shared breakfasts. I will remember the picture of Akwasi Mclaren standing out as the man in action, moving around and being there for his guests one at a time. I will remember him coming to our dining table with an antihistamine for Mercy because she had reacted to an ingredient in the food. I will remember Flo, another lodger and the good doctor scurrying over with his travel group to care for Mercy. And when I think of the Travel Tribe, I will remember not just the places we visited but the journey we took together, the road trips, the stop at God is Love Chopbar at Takoradi, the conversations on the bus, the sing-alongs, Efua’s singing wafting into my Instagram recording, meeting Sheila of the travel tribe.

Of course, it’s good to plan. It’s also great to go to places for its landmarks and sights. However, this Ghana experience is very special to me, and I would not give it up for anything. Yes, Mawuu had shared the Travel Tribe’s plan of visiting Escape 3 Points with me, but I honestly didn’t read anything in the chat group. If not, I would have known to go with my Ankara for the 31st dinner.

On the eve of 29th December at Escape 3 Points, Mawuu asked us what we hoped to get out of this trip, and I said something about wanting to get out of myself and feel more comfortable with other people. I had made that up on the spot, but perhaps it wasn’t far from the truth. Perhaps, if I had also said I wanted to slow down, that may have also been close to the truth. But the truth was that I hadn’t thought of anything I had hoped to get out of the trip.

Reflecting on this trip, I think just like Derek Sivers and Amit Chaudhuri, my purpose of going to Ghana was to meet the people I’d had the pleasure of meeting – Mawuu, Eyram – the travel tribe – Sheila, Efua, Mercy, Kennetha, Ama, Nana, Prynx, Fui, Kwaku, Pearl, Jenny, Kelechi, Whiskey. The guests I had connected with at Escape 3 Points – Sol, Flo, Artis3, Eva, Charley, Nyash; the cheerful staff at the wondrous lodge and Akwasi Mclaren.

And these conversations with these people who have become a family I never knew I needed are precious memories I cherish. Meeting them and knowing them, interacting with the places I visited, writing the story of Escape 3 Points, meeting me again.

Travelling means finding new inspirations because when the thought of writing a story about this place came like a guest during my Yoga with Efua, Mercy and Sol, I watched it as it made its visit. The thought flitted around, then came again and again until I made sense of it. Still, never in my wildest dreams had I imagined making a video until the interview day when Eva accompanied Akwasi with her phone and a tripod.

Travelling means finding new experiences. It means finding new perspectives. It means finding new adventures. It means finding memories and creating lasting impressions. It means finding connections and building relationships across cultures. It means finding more about oneself. Because in travelling, you take pieces of yourself to foreign places where you meet other people who have also brought pieces of themselves. Travelling offers us a chance to start all over again with others without preconceived notions of who we are or who they are. Doyin says, “travelling makes you a new person,” and I could not agree more.

PS: You can watch my travel highlights on my Instagram, or read my interview with Akwasi Mclaren about the Escape 3 Points story on Creatives Around Us.

I am grateful for writers like Brene Brown, who are able to share meaning with us through their writings.

“…this is what I’ve found. To let ourselves be seen, deeply seen, VULNERABLY seen. To love with our whole hearts, even though there’s no guarantee, and that’s hard. To practice gratitude and joy in those moments of terror, when we are wondering ‘Can I love you this much? Can I believe in this, this passionately? Can I be this fierce about this?’ Just to be able to stop, instead of catastrophizing what might happen, to say, “I’m just so grateful,” because to feel this vulnerable means I’m alive.”

Brene Brown on The Power of Vulnerability

The following are what fills my heart with so much warmth today – going on today’s run and my soul sister, Sheila Adufutse.

Coach Bennett always says to look for joy in every run.

Today, I went on a run with Nike Run Club Coach Bennett and Headspace co-founder Andy Puddicombe on the A Whole Run, and throughout the run, I kept thinking about this phrase – look for the joy in everything. Look for the lessons, look for the thrill, look for the excitement, look for the discovery.

I learn a lot from my runs. This particular one taught me that I am a new person every time I experience something again. It reinforced the topic of setting a new intention with any activity. Before this run, I had fought with my will to move my body to go for a run.

In the Gospel of Nature’s designers’ catch-up last Tuesday, I learned from Chine that I am anything I call myself. I don’t have to be a professional to call myself a designer. If I can use design tools to create a beautiful design, and I say I’m a designer, I am a designer. If I say I’m not, I’m not.

When going for a run, I always tried to hit a better pace than the previous one. I had felt that this way, I could call myself a runner.

But as I hit a new 1k on this run, I reminded myself to go slowly and not focus on the pace, but on my intention. I kept my body and mind in sync with the purpose I had set out for this run, urging my body forward and reminding myself that this run does not have to be perfect.

With every run, I learn the joy of being a beginner. I started running in 2020; I have gone on about 70 runs. On each run, I see how much of a beginner I am; this teaches me that any activity can come with many possibilities.

I am also grateful for Sheila Adufutse, my soul-sister. Today is her birthday. Sheila was the first person that taught me to slow down. We have never met because she is on the other side of my world. Sheila lives in Ghana while I am in Nigeria, but it feels like she is close to me. I am thankful for her friendship that keeps giving; hers is one that accepts me for who I am. Sheila shares opportunities and lessons with me and constantly teaches me that I am okay, I am doing well, and I am enough.

I am thankful for your kindness, love, patience, and being Sheila. Because being Sheila means being someone your friends can rely on – you are a Godsend.

And to sum up my gratitude, I want to share my lesson from this week. When we allow ourselves to be a beginner with any activity, we create the space to learn and do things even though we are afraid. We embark on the exercise with the thrill of discovery, without facing the weight of our expectations.