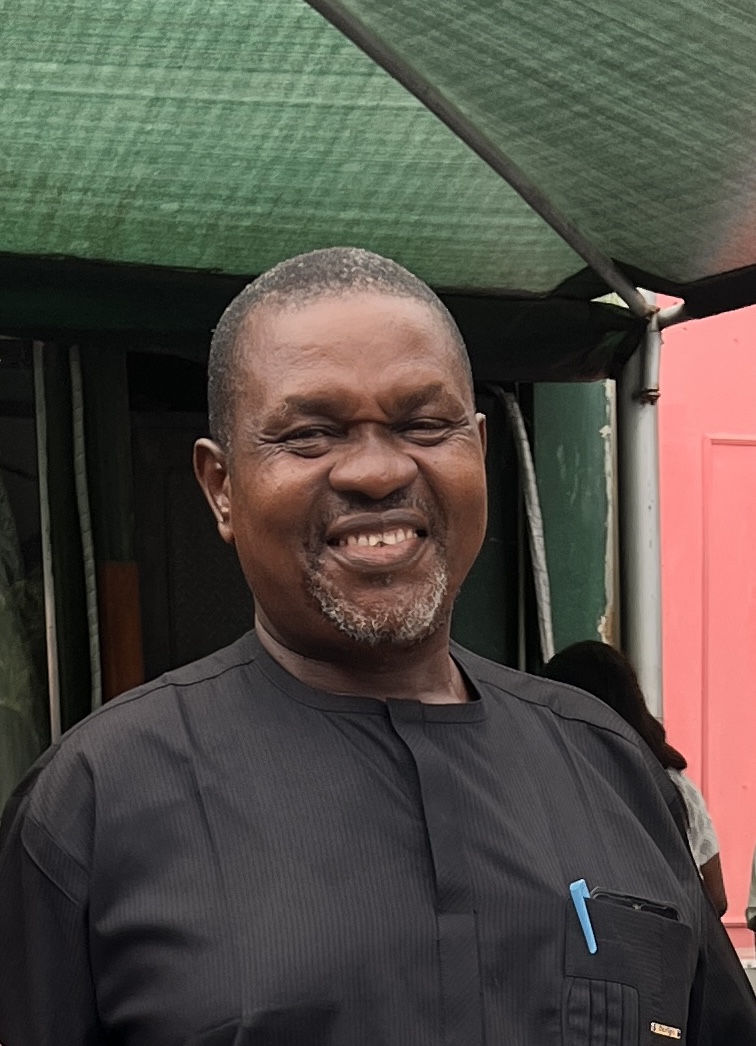

The cause of my father’s death was cardiac arrest, they said.

For months, I’d replay these horrific words in my head. ‘Ifunanya, daddy anwuola.‘ ‘Ify, they confirmed him dead. They said it’s cardiac arrest.’

I would replay those words in my head until I began seeing the lettering on the walls. ‘Daddy is dead.’

How is daddy dead? He can’t die. I have never imagined him dying. And perhaps that’s where the problem is. The ‘not seeing.’ That’s why I can never forgive myself. Never imagining him capable of dying.

That’s why I couldn’t see him. Didn’t see him calling out to me.

July 20, 2025 started like any other Sunday. I’d gone cycling. I was pleased with my ride. Then came the feeling that I was missing something. Something very important, but I couldn’t put a finger on it. I was unsettled. I kept turning in my bed, putting off the series I had planned to watch.

Earlier, I had felt a momentary unsettling in my soul. I don’t remember when this was. Was it the same day? The day before? But I remember being in the shower and saying ‘why do I feel like death is upon me?’

For days, I would not forgive myself. Why did I mutter out loud ‘death’ without stopping to think about my dad? Without even considering that the warning could be about him. As the wedding drew near, I worried about what could go wrong: my pregnant sister being alone as everyone attended without her. I was always worried about something bad happening, but never did I worry about losing my dad. Never.

After the news came, I was frantic. I screamed. Tore at my hair. Ran into the bathroom and threw myself on the ground. I kept tearing at myself, crying that it should be a lie and if it were true that something had happened, let it be something minimal. Maybe he fainted or had a heart attack. I promised my daddy and his chi that if he could come back to me, I would do anything. Anything.

I think about how alone he must have felt in his last moments. To have collapsed with nobody around. How long did it take for the children to find him to raise alarm. Why was it hard to get a vehicle or an ambulance to take him to the hospital? From Lagos, we phoned my mum’s brother, Uncle Chigozie. I remember crying into the phone in inaudible tones, ‘uncle, please, I don’t know what they’re saying. Please go to Umuhu and take my daddy to the hospital.’ Umuhu from Agboana is about 10.3 km, but the rains made the roads impassable, and getting there took over 30 minutes — and more than 40 minutes to get him to Nnamdi Azikiwe University Teaching Hospital (NAUTH). The same NAUTH that pronounced my mother dead. I cannot believe it.

Uncle Chigozie said ‘Ify, they confirmed him dead. They said it’s cardiac arrest,’ and I didn’t hear the rest of what he said. I think I threw the phone away.

Perhaps this is my punishment. Perhaps this life is my hell. Perhaps, I brought all of these upon me.

I wake with a start every morning and then I realise what I have lost. I wake up, and then it dawns on me that I’m never seeing my daddy anymore. I go to sleep, willing him to find me in my dreams. On most days, I am gripped by the fear that I might be suicidal; I’m terrified of what I would do if I feel terribly alone, the way I do when the realisation of my father’s passing hits me. I look for my father in many things. Nature, birds, trees, strangers, Shalvah. And if I dared to imagine that I might reflect his essence, then on the days I look into the mirror and catch even a glimpse of him, I realise I am my father’s daughter. I lean into that feeling. I do not understand why it took me so long to recognise his face in mine.

Days after daddy passed, I was unable to sleep alone in my room. Not only for fear of what I could do to myself, but also in fear that my daddy would appear and flog the life out of me. For not remembering. I deserved it. And somehow, I wanted it. That punishment. Or forgetting that I ever knew him. It would be better to forget him entirely so that it didn’t hurt so much.

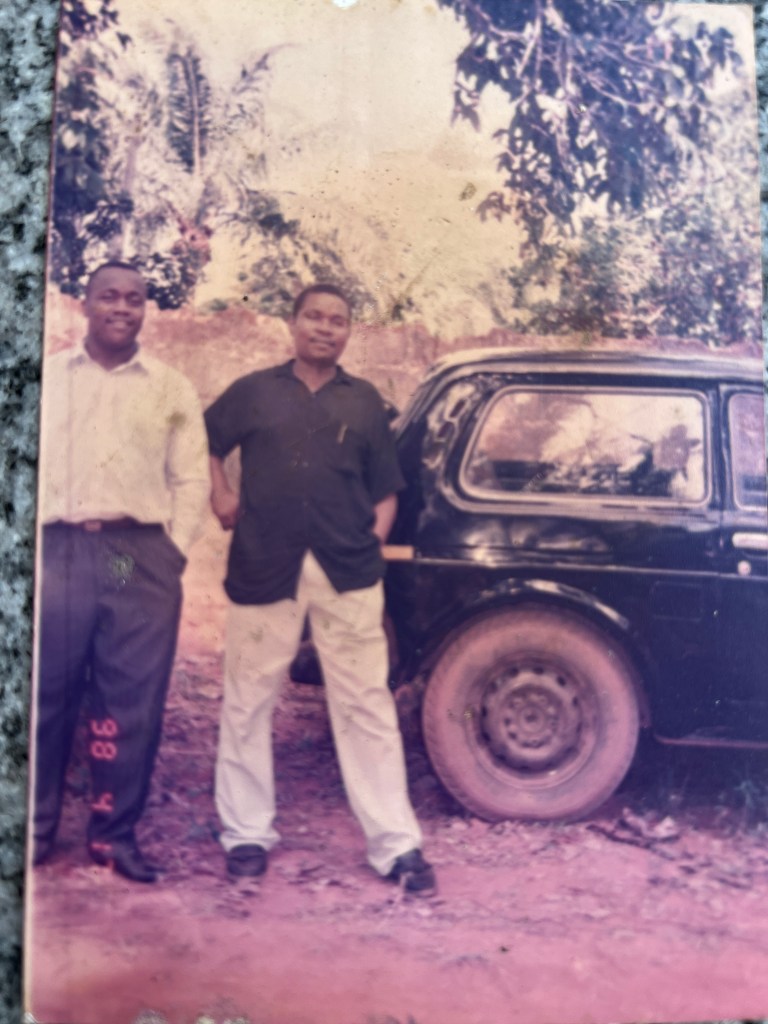

But I forget that my daddy is not one to punish or to bear malice for another. He was never like that in life, how could he be something else in death? My dad was so soft-spoken, his voice was not good for shouting. If he shouted, you could hear that he was tired. He never believed in flogging children, because he saw it as evil. There are other ways to raise a child than treating them like animals, he said.

I forgot that my dad saw me. He loved me, even though he never said the words. We had our misunderstandings, but I can clearly see his actions now, the things he did to please me that I never acknowledged. Oh, what a curse it must be to be a parent.

Most times, my breath escapes me. I would sit beside myself and weep. My tears betray me, breaking out of my body from a silent longing into a heavy lamentation. And my husband catches me every time. ‘My husband.’ My daddy only met him once. That February, I took Shalvah to see him.

I had initially planned to bring dad to Lagos for a check-up in June. Then Shalvah wanted to visit, so I thought I could bring him earlier in Feb so we could have a family meeting when Shalv was around. But Shalvah wanted to visit my hometown and didn’t want my father to go through the trouble. Then I left it for June.

The wedding planning took up my mental space. That, with other things I can’t remember right now. Because how did I suddenly forget? How did I then schedule for him to come to Lagos on the 5th of August for my wedding happening the 7th? When was he supposed to rest? Why didn’t I see my daddy as an elderly man who should not be making that long journey, but should rather be with us at least a month before the wedding? Then this tragedy could well have been averted.

With all the times daddy called out to me, I didn’t listen. Did he know that I love him?

On Wednesday 23 July, I stood before the body that belonged to my daddy. This is the first time I referred to it in that manner. Because I want to believe that my daddy is not reduced to the body lying helpless in that mortuary. I had gone expecting to be punished, while hoping I could somehow connect to my daddy to tell him how much I loved him. To tell him I was sorry. To express my heart before him. As I stood before him, with all the emotions that came breaking out of my body — as I came undone — I felt a blanket of peace enfold me. I leaned into this feeling as I wept before my father, my dearest daddy who gave life to me. I didn’t know what that feeling was. Was it my dad letting me know he loves me? He understands me? He’d forgiven me? That I am his child forever?

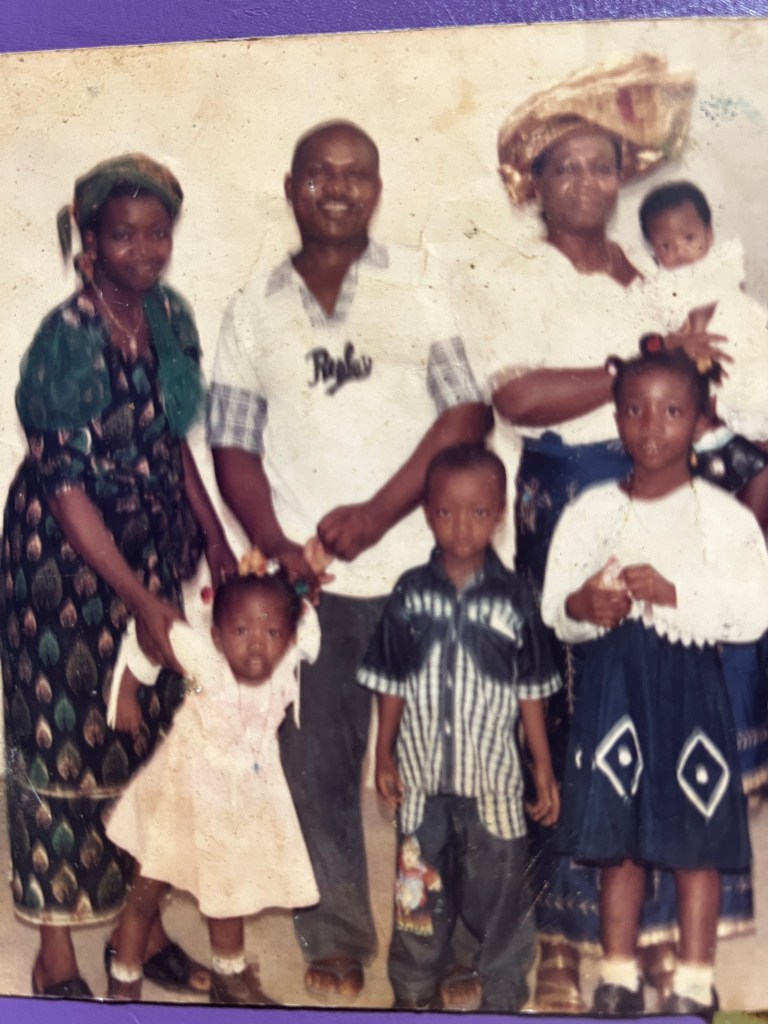

Mawuu said a parent’s death yanks the ground from beneath one’s feet. I felt the earth shift beneath me the night Newman and I visited my father’s house, my village, my ancestral home, after we had been to the mortuary. We arrived at the gate as my heart thudded, not knowing what to expect. Walking down, I saw my uncles gathered around, but not my daddy. Someone else occupied the seat where my daddy would normally sit. It felt overwhelmingly terrifying to take another step forward.

My uncles watched as we walked towards them, and I felt as though the ground itself dared us to continue. Home does not feel like home anymore. I stopped. My breath escaped me as I replayed my mother’s voice welcoming me, then my grandmother sitting far in front of the obi, waiting for my return with arms outstretched and beckoning me as she called out ‘Ivee,’ and my daddy sitting by his bike beside his house as I went to greet him, saying ‘ehen, nnua.’ Home no longer feels like home. I walked by my father’s motorbike to the kitchen where my mother used to cook for us. There was no longer anyone to welcome us — not mummy, not mama, not even daddy. One of my uncles asked why we were walking like strangers. How do we not feel like one when the earth beneath us has been yanked off?

I am grieving, still. It feels like a lot of time has passed, and I should have got over it, but I am not over it. I grieve for all of the words I never said to him: the missed chances to right every misunderstanding, the hurtful words I said to him without meaning any single one, the love I never poured into him. I grieve for Munachimso, my sister’s baby, who arrived without ever meeting her grandfather. And for my father, who was truly proud of his daughter.

For most of the past eight months, I wrote in my journal. lamentations to my dad, suicidal notes for myself, and pleas to the universe to bring him back to me. I was numb as I interacted with people, attempted to show up for myself and my family, though not successfully, and every day as I put one foot in front of the other, I asked myself the same questions. I hid from my friends, from social media. I realised I am running from myself, driven by an overwhelming feeling of shame and guilt. In all this time, I had my husband and my friends remind me that I am worth it. Amakanwa and Shalvah would stay on the phone for hours while I worked and cried at the same time, affirming and advocating for me. Sometimes, we cried together. I felt my husband’s touch and loving kindness. I didn’t think I deserved anyone’s kindness, but Amakanwa’s words remind me that I am worth saving:

‘My dearest Ify,

I am writing this for you, for now, for your heart, for mine, and for the days ahead. Because life keeps turning, and pain, like joy, never truly leaves us. We live in a world where beauty and heartache walk hand in hand, the same life that fills our hearts with giddy love and laughter is also the one that brings us to our knees with grief, longing, and quiet rage.

It seems this is part of our fate in this incarnation: to love with our whole being, to give and receive love in all its splendor and then to mourn it when it’s taken from us. And I wish I could tell you why. Sometimes, I feel I would rather have been untouched by love than to feel its absence so deeply.

I still carry that soul-deep ache for my mother. After all these years, I still long to see her, to hear her voice again, to touch her face, just to be reminded that everything is okay. But life has taken that from me, and in its place, a quiet pulse of absence lingers. It never fully disappears. Yet, Ify, it does get softer. One day, the pain won’t feel as sharp, won’t steal your breath in the morning. One day, you’ll remember your father’s voice, a phrase he often said, and you’ll smile instead of weep.

His memory will become a sacred ritual, keeping him alive through your words, your thoughts, your everyday gestures. You might find yourself speaking about him more, or even writing a book to preserve his essence. These rituals help us give shape to our grief and remind us that the gaping hole in our hearts is real, and that love this powerful demands remembrance.

And one day, Ify, your child with Shalv will look up at you with a certain expression, and in that moment, you will see your father, and maybe your mother too. And you will cry out, “Nna m o!”, with tears in your eyes but a smile on your lips. And your spirit will speak out loud, thanking those beautiful souls who gave you life. And somewhere deep within, they will thank you too for being their Adaọma, for stepping into the responsibility life placed on your shoulders long before it should have.

And so, Ify, for this moment, for this unimaginable loss, I pray with you:

Ozoemena, may this never happen again.

From now on, your Chi will walk more closely with you. May your spirit be sharpened to hear the messages you need to receive. May you be surrounded by divine protection, and may the power of your love and prayer push back against every dark force that tries to touch your family. Because when our love has gathered enough power, when our grief becomes light, we have the strength to say: “Ọ bụghị ugbu a, ajụ m ajụ.”

I love you, Ify. And I know you are surrounded by love from your husband-to-be, your siblings, your extended family, your friends. You are being held in prayer, in thought, and in the boundless love of God. His love surrounds you now and always.

You have suffered an enormous, unspeakable loss but somehow, you will carry on. Ụnụ niile! You and your siblings will go on to do mighty things. You will carry your father and mother with you into every victory, every joyful moment. And the world will know their names through what you become.

Ndo, nne m.

Ọ ga-adị unu mma.

Ike agaghị agwụ unu.

Chukwu gozie unu.

Amen❤️‘

My husband holds me every time I say to him that I don’t deserve sunshine. He says ‘No, you deserve it a thousand times over.’ ‘You did your best.’ I wondered if he was saying those words just for the sake of saying them, but I’ve come to see that he truly meant them. How could he see me better than I see myself? Perhaps that’s what love is.

I remember counting down to the wedding. I was so excited and couldn’t wait to have my daddy at the venue. I wanted to show him off and introduce him to my friends. I wanted him to see how Shalvah loves me. But it never happened.

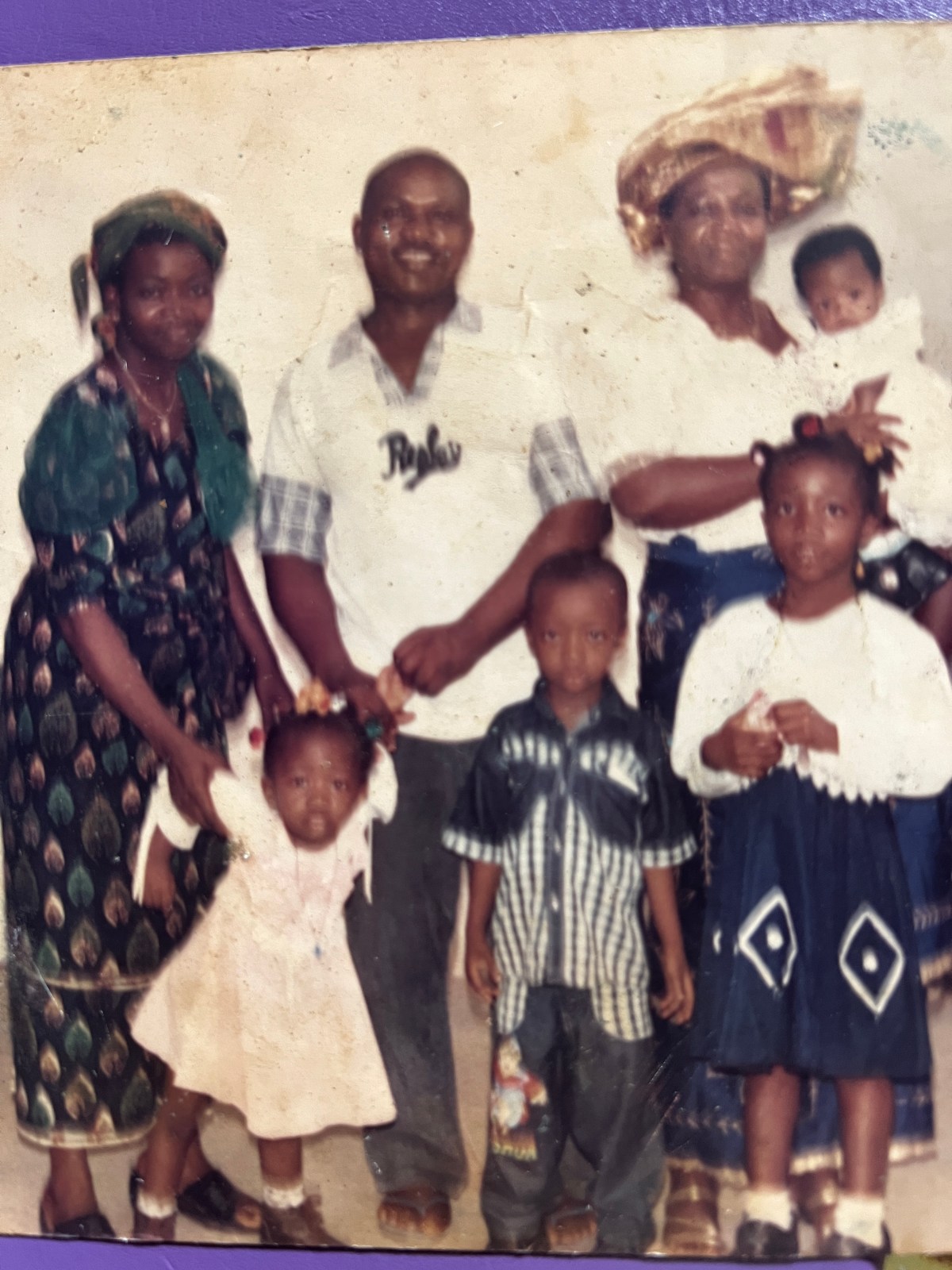

At the court wedding, my younger brother Newman stood in for my dad. Daddy’s photo frame sat in a seat reserved for him. Shalvah had gone above and beyond in the final planning. After my dad passed, my strength waned. Relatives phoned to say the wedding should go on, but I had the last word. I didn’t know what I wanted. The wedding will go on because daddy was so excited about it. Was that the truth, or did I continue with it because I was selfish? Shalvah reorganised the event by including a memorial for him, opening our guestbook with photos of my daddy and family. I was stupefied by the care and planning that went into it. I have a lot to be grateful for to our friends who helped make that day, yet I haven’t found the words.

I do not remember much about the traditional wedding, just that I didn’t want to be there. It didn’t feel right to be celebrating in my hometown when my dad’s body lay cold in the mortuary. I moved through the rituals, unsure of how I was feeling, while I felt everybody’s gaze on me.

On October 5th, I dreamt about my daddy. It was the first vivid dream I had of him. He was as I remembered him: young, active, repairing his clients’ electronics. He cooked. He moved about his house. I watched him walk. In the dream, I didn’t know he had died. But there was a moment when I remembered he had a heart disease, and so I wanted to schedule some time for him to see a cardiologist. I knew one, I remembered in the dream. I just need one day, I said aloud to myself: ‘Daddy, I just need one day.’ I’ll take you to the cardiologist and you’ll be fine. In the dream, it felt like he was a walking bomb. I wondered when he would detonate. And if I could do something, maybe I could alter time. In the dream, he was my daddy. And I was his daughter. I believe that was the night we conceived our baby.

Until I find my voice again, until I can smell the familiar in the forest, see the yellow in the roses, the spirit in a structure, and the wonder in the countryside, I will hold onto that conception dream. I will lean on my husband, who has lent me his eyes to see the colours through them.